Dome grotto 3, 2025. Oil, oil stick and dry pastel on linen. 129 x 190 cm.

Dome grotto 2, 2025. Oil and pastel on linen. 149 x 102 cm.

Dome Grotto 2024. Oil and pastel on linen. 123 x 177 cm.

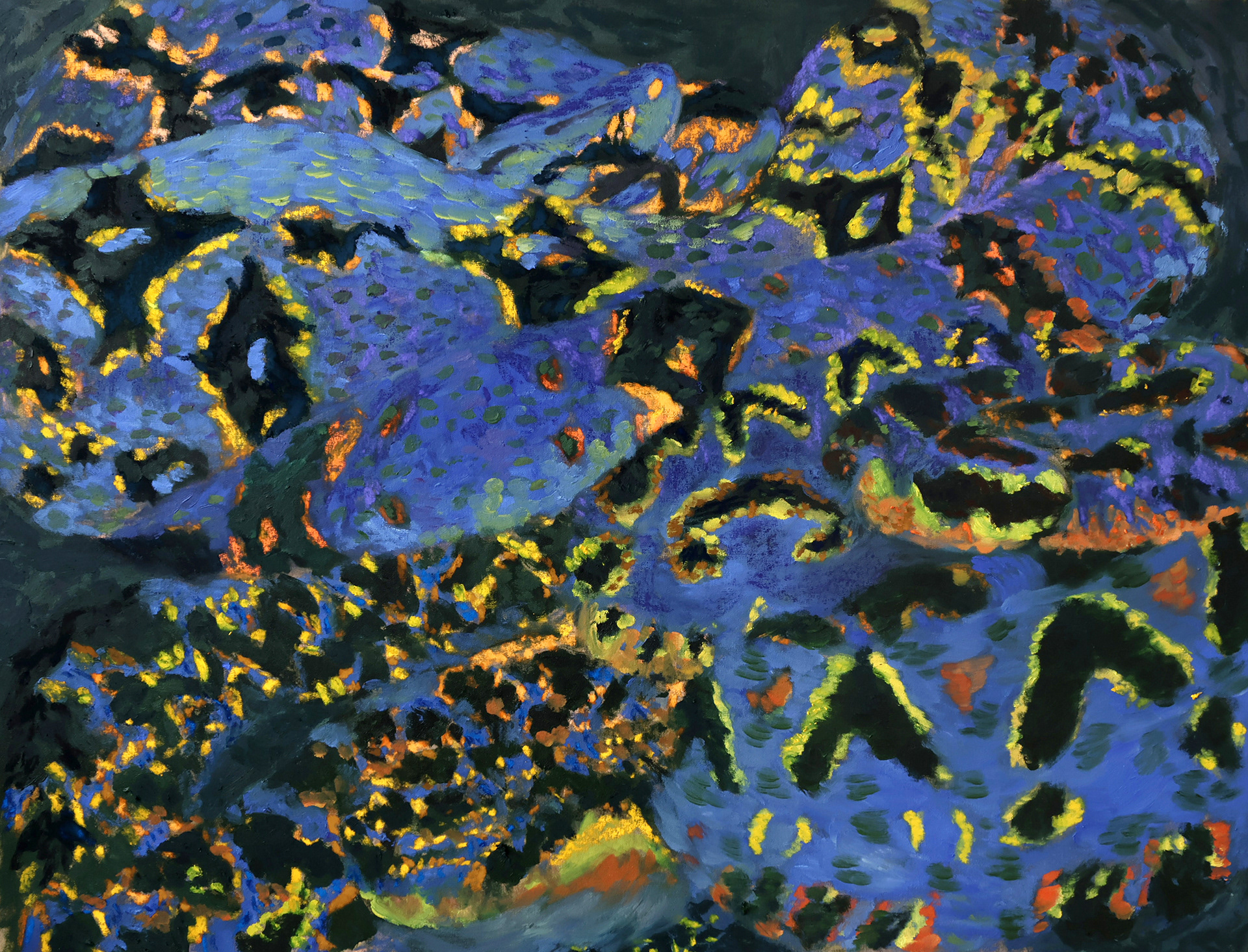

Urdidura, 2025. Oil, oil stick and dry pastel on linen. 98 x 130 cm.

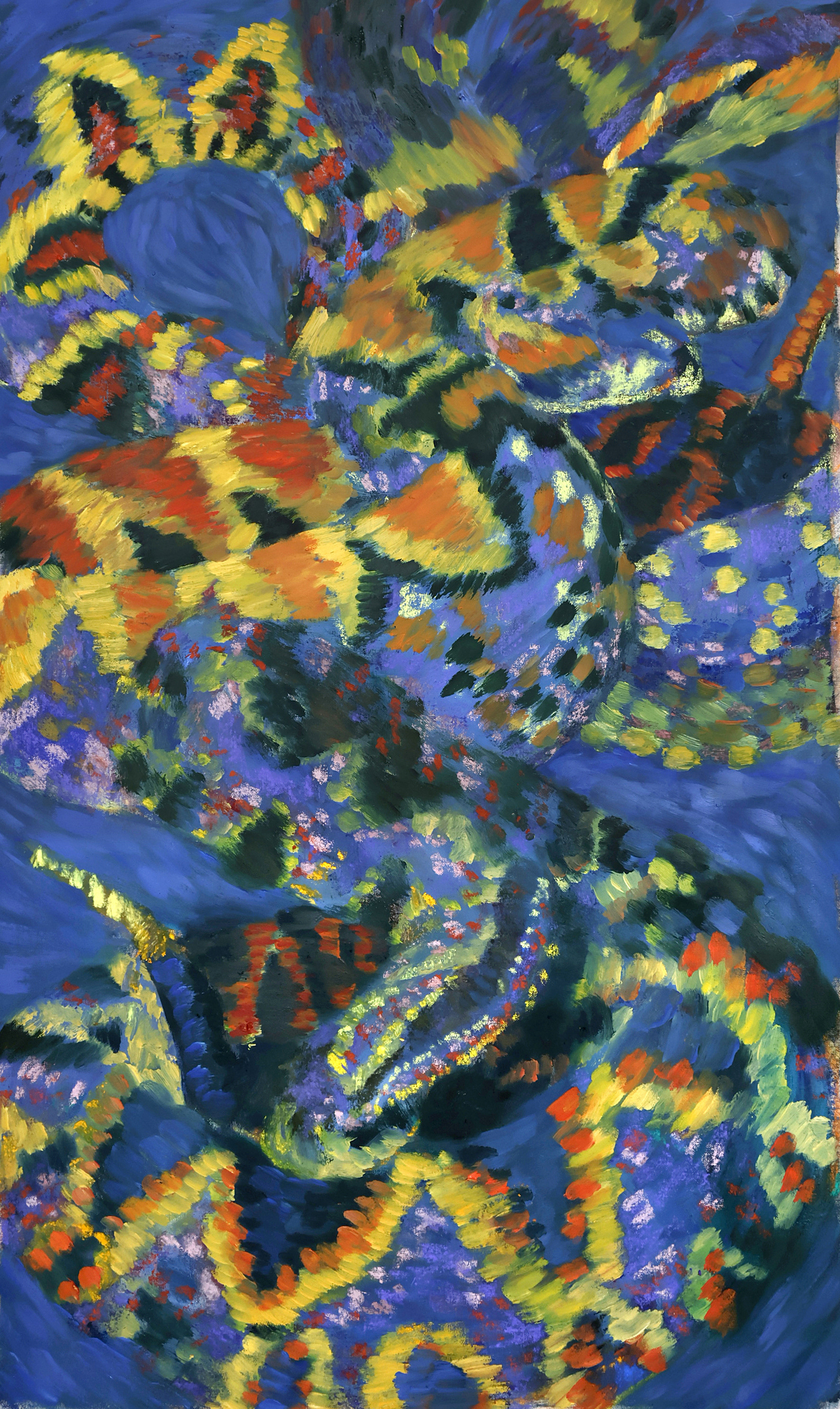

Sob o ciúme do céu, 2025. Oil, oil stick and dry pastel on canvas. 132 x 78 cm.

Sem retorno ao paraíso, 2025. Oil on canvas. 143 x304 cm.

Alma do mato 3, 2025. Oil and pastel on linen. 182 x 124 cm.

Mensageiros, 2025. Oil and pastel on canvas. 90 x 50 cm.

Anseio original, 2024. Oil an and pastel on linen. 124 x 268 cm.

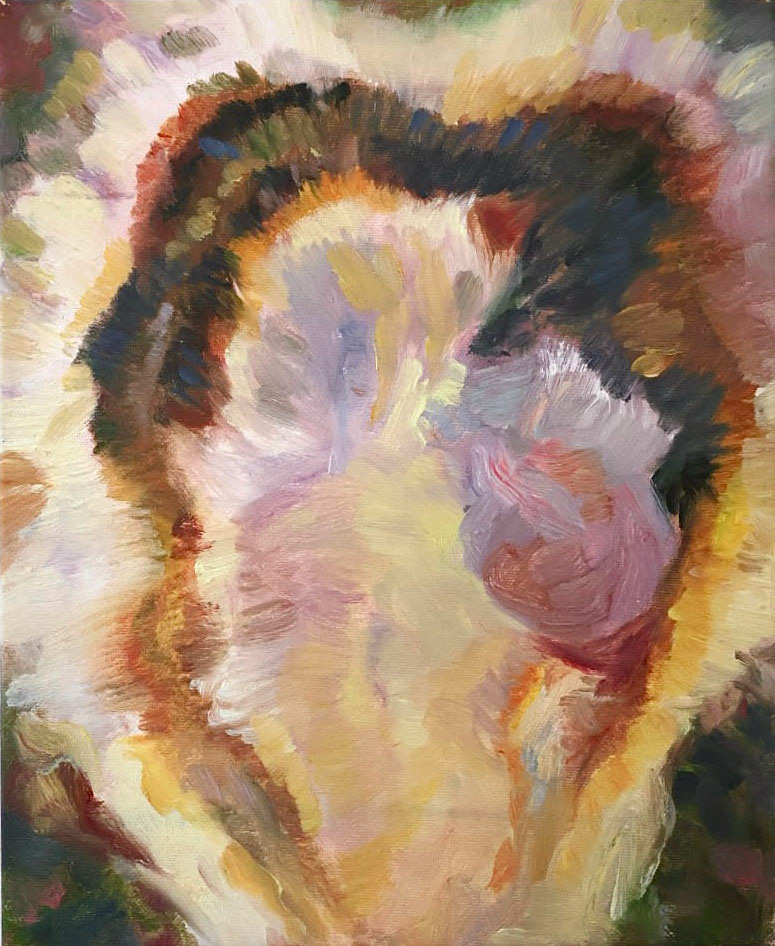

No title, 2025. Oil on canvas. 30 x 20 cm.

Alma do mato, 2024. Oil on linen. 125 x 204 cm.

Cido, 2023. Oil on canvas. 174 x 288 cm.

Mensageiros, 2024. Oil on canvas. 140 x 160 cm.

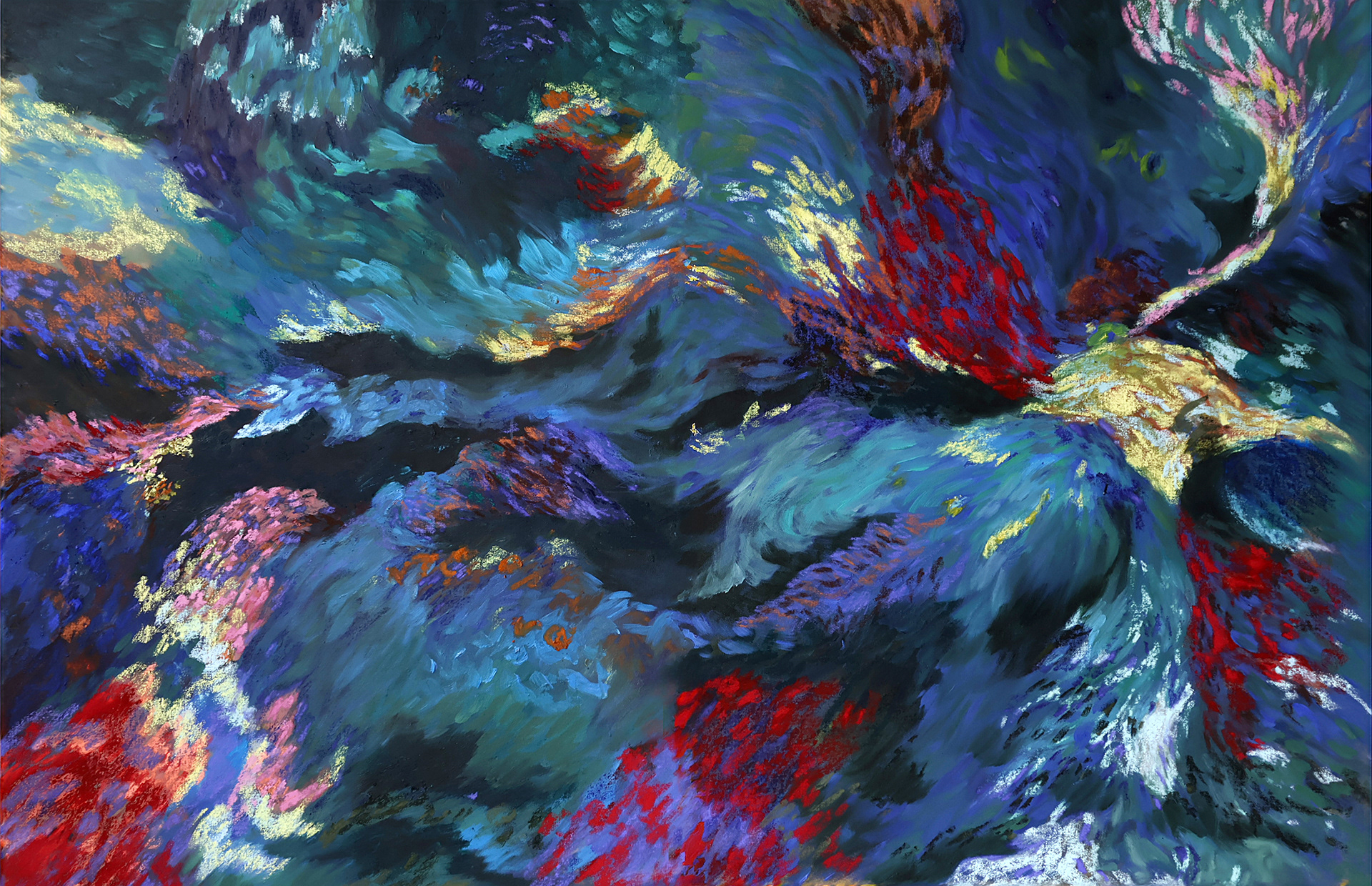

rio-música, 2024. Oil and pastel on linen. 122 x 170 cm.

Olhando para o chão, 2024. Oil on linen. 191 x 122 cm.

Anseio original 4, 2024. Oil and pastel on canvas. 26 x 37 cm.

Anseio original 3, 2024. Oil and pastel on linen. 195 x 124 cm.

Anseio original 2, 2024. Paste and oil on linen. 90 x 120 cm.

Os ventos falam, 2024. Oil on linen. 125 x 200 cm.

140 dias de Sol, 2024. Oil on linen. 127 x 205 cm.

Where the earth and sky mix and mingle, 2022. Oil on canvas. 200 x 130 cm.

Cynara n2, 2023. Oil on canvas. 155 x 205

Cabiria 2, 2022. Oil on canvas. 30 x 22 cm.

Coração , 2023. Oil on canvas. 155 x 205 cm.

Ray, 2022. 200 x 130 cm.

Mantequilla, 2022. Oil on canvas. 125 x 155 cm.

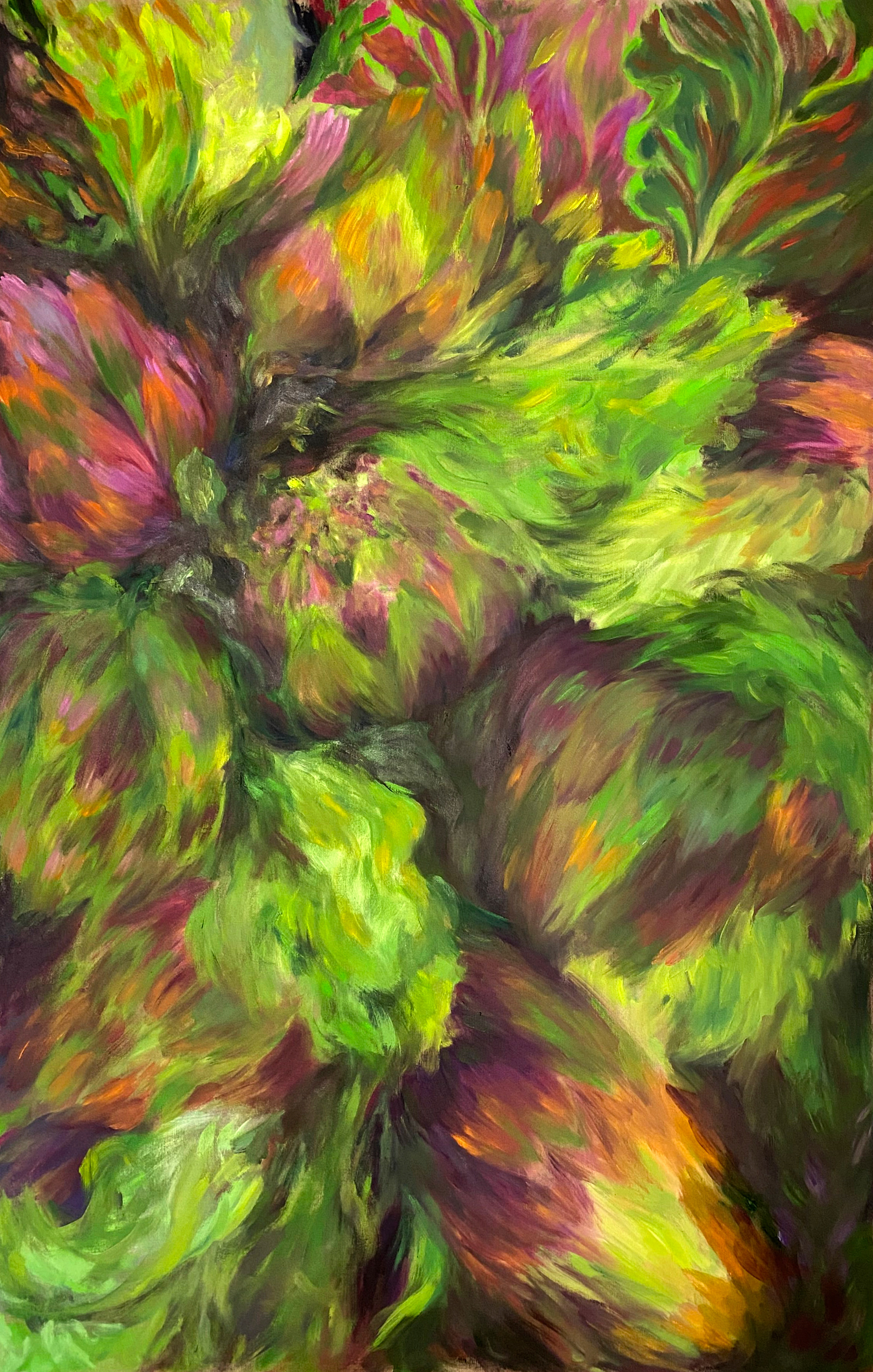

Cynara, 2023. Oil on linen. 94 x 130 cm.

Alma do mato, 2022. Oil on canvas. 125 x 155 cm.

Cabiria, 2022. Oil on canvas. 120 x 200 cm.

Terra, 2023. Oil on linen. 150 x 110 cm.

Avant la terrine, 2022. Pastel on paper. 23 x 30 cm each.

Butter for Turner, 2023. Oil on linen. 200 x 130 cm.

Cyril, 2022. Oil on linen. 140 x 200 cm.

Ray n2, 2022. Oil and pastel on canvas. 48 x 59 cm.

Milharal crioulo, 2023. Oil on canvas. 140 x 220 cm.

Sorte, 2022. Oil on canvas. 31,5 x 47 cm.

Viande danse, 2022. Oil on canvas. 125 x 155 cm.

Yellow oyster, 2022. Oil on canvas. 43 x 25 cm